by Derek Morrison, 6 February 2010 (updated 10 & 23 February 2010)

N.B. Any personal views expressed in this posting are those of the author alone and should not be construed as necessarily representing the view of any other individual or organisation.

In their two new well-researched productions both the US PBS and the UK BBC/OU are individually but synergistically creating a wonderful set of resources for students of the digital world and for those generally interested in the impacts of the internet and the web on our lives. Apart from the high quality content and supporting resources both the PBS and BBC/OU productions have, in different ways, adopted a welcome multi-platform “open” approach which means that the broadcast and archive materials become part of a much richer resource by including blogs, user generated content or pre production commentary, and repurposing of some material from the productions for non-profit educational purposes is actively encouraged. At the moment, however, I think the educational merit gold star should be awarded to the US production.

The US production is not intended to be a stand-alone documentary. It is instead part of a longer term project called Digital Nation: Life on the Virtual Frontier. The Digital Nation initiative is part of the US public television’s flagship public affairs series Frontline which specialises in in-depth investigative pieces and quality film making. Digital Nation is Frontline producer Rachel Dretzin’s long-term project exploring and trying to understand:

… the implications of living in a world consumed by technology and the impact that this constant connectivity may have on future generations … I realized that no one seems to know where all this technology is taking us, or its long-term effects. (Rachel Dretzin, Producer/Director, Digital Nation)

The keynote Digital Nation documentary was transmitted on 2 February 2010). Although the overall documentary is 90 minutes long and is worth viewing in its entirety on a first viewing, the project web site also offers streaming videos of extended interviews with Francoise LeGoues (IBM), Clifford Nass (Stanford University), Noah Shachtman (Wired editor), and Sherry Turkle (MIT), plus a method of accessing each one of the nine video chapters of the overall video (see below)

The Digital Nation project offers a much richer supporting web site than the BBC’s production. For example, the former includes a media wall where contributors are invited to upload their personal accounts of how the internet has impacted their lives to a zone named “Your Stories whereas the BBC’s “open” documentary experiment appears to have focused more on pre-production user comments and feedback to help shape the programme. In contrast, the US approach enables users to more easily add direct value to the framework provided by the professionals; plus the Digital Nation web site’s synchronisation of hyperlinks with each section of the video stream merits another value-added point. The Digital Nation video can either be watched in linear fashion or by randomly selecting one of the nine chapters making up the production, i.e.

- Distracted by Everything?

- What’s it doing to their brains?

- South Korea’s gaming craze

- Teaching with Technology

- The Dumbest Generation?

- Relationships

- Virtual worlds

- Virtual experiences change us?

- Where are we headed?

N.B. I couldn’t provide direct hyperlinks in the above chapter list because a custom Flash plugin is being used to provide that function. Be aware also that the individual chapter acess facility is only apparent if you access the video VIA THIS LINK (apologies for the shout out). I accessed the Digital Nation video via another route in the site and was forced into viewing via the linear mode and I want to save Auricle readers that particular pain of discovery.

Chapter 1 of Digital Nation: Distracted by everything? and Chapter 2: What’s it doing to their brains? kicks off proceedings by highlighting the concerns being raised by leading internet luminaries such as Douglas Rushkoff, MIT’s Sherry Turkle and Stanford’s Clifford Nass about the worrying outcomes arising from our use and potential abuse of technologies including the much trumpeted multi-tasking behaviours of the so called “digital natives” having seriously negative consequences for learning. In particular note the apparent chasm between the confident self-perceptions of the digtial natives about their multi-tasking abilities and the emerging evidence.

Virtually every multi-tasker thinks that they are brilliant at multi-tasking … You know what! It turns out that mult-taskers are terrible at every aspect of multi-tasking … They get distracted constantly. There memory is very disorganised … Recent work we have done suggests that they are worse at analytical reasoning … We worry it may be creating people who are unable to think well and clearly … (Clifford Nass, Stanford University)

If we are going to deal with the problem of distraction, it’s somthing we are going to have to do together … Maybe it’s time to press the pause button. We need to know if we are tinkering with something more essential than we realise … It’s changing what it means to be a human being by using all this stuff … (Douglas Rushkoff)

In Chapter 3 of Digital Nation Rushkoff goes on to look at the internet addiction problems that have afflicted South Korea and the response of the Korean government which has taken the concept of digital literacy to a whole new level.

Over the last 20 years, however, the web has moved from something one does to the way one lives; connected all the time. And it appears that far more of these (South Korean) kids than I would have thought are overwhelmed … but they are also taught something else, how to use computers responsibly. It’s required for Korean students starting in the second grade … (Douglas Rushkoff)

Chapter 4 of Digital Nation focuses on Teaching with Technology and the Chatham High School example of an inspirational headteacher turning around a failing school implies that it’s the use of technology which remotivated staff and students. However, the enthusism is tempered by:

My concern with this digital media is that it’s such short attention span stuff that they get bored. It’s what I call instant gratification education, a thought comes to you, you pursue it, you see a web site you click on it. You want to hear music while your studying you do it. All this bifurcates the brain and keeps it from pursuing one linear thought and teaches you that you should be able to have every urge answered the minute the urge occurs (Todd Oppenheimer, Author, The Flickering Mind).

However, back in Chatham High School one teacher says:

I think there is something to be said for multi-tasking. I think teaching students to multi-task is really important for their future jobs.

And the headteacher reinforces the view with:

I think the world has sped up in a lot of ways; and education hasn’t

Chapter 5 of Digital Nation is informed by Mark Bauerlein’s book The Dumbest Generation? and it kicks of with an articulate student owning up to never reading books and relying on plot summary services like SparkNotes to enable him to read Romeo and Juliet in five minutes.

And the consequences of such grazing on such convenient “information objects” some believe are?

You already hear professors and others talking about the way kids write, so that instead of writing in essay they write in paragraphs. They write a paragraph and then they say ah now I’ll look at Facebook for a while or they write a paragraph and then oh I’ll play poker or I’ll do all of these at once … So what we are seeing is less of a notion of a big idea carried through and much more of little bursts and snippets. (Clifford Nass, Stanford University)

And should we be anxious about our students not reading books? Some Digital Nation contributers offers some reassurance.

We confuse the old ways, the best ways of doing something once with the best ways of doing something forever … It’s not that kids shouldn’t learn to communicate. It’s not that they shouldn’t learn to express complex ideas … those are what we call the verbs. The nouns that they use whether that’s the essay, or the paper or the ray or whatever. Or whether it’s the video, or the podcast that’s what changes. The learning may stay the same but we invent new ways of teaching and I don’t know that if the book which was for a long period of time, but not that long … is the best way [of learning] in the 21st century (Marc Prensky)

There was always gains and losses … when print replaced aural culture, when writing happened there was certainly things we lost, one of them was memory. You think of the Homeric poems, The Iliad and The Odyssey. The Homeric singers could produce thousands of lines of poetry out of their own memory. We’re not good at that any more because print took it away. Is it a loss? Sure. And to a certain extend getting people to be contemplative and a little bit slower; not to multi-task all of the time, paying avid attention over a long period of time to a certain extend might be lost. But that’s the price of gain. (James Paul Gee, Arizona State University)

The point is that this is a problem that we as human beings have coped with throughout most of the 20th century and into the 21st century and the good news is we survived it. As a culture we learned how to adapt to it … so we are seeing this period of evolution and at the end of the day we’re better off as a society if we go at this with a sense of open mindedness and exploration. (Henry Jenkins, University of Southern California)

Chapter 6 of Digital Nation focuses on relationships.

The key example in this section is the 83 year old grandmother who with her grandson has developed a “hit” home cooking streaming video web site and agony aunt (grandmother) facility which undermines the conventional view of the old as excluded actors in the digital revolution. Rushkoff highlights that the grandmother featured is “using the net to simulate a sense of connection that people had with their own grandmothers” but he segues neatly into the world of online games like the World of Warcraft.

There are people trying to inhabit the net as though it was a real place (Douglas Rushkoff).

Games do give people a powerful vicarious life (Henry Jenkins, University of Southern California)

But what was interesting in this segment of Digital Nation was that in comparison to the South Korean experience in the US the community building and co-operation aspects of online game playing seemed to be in the ascendant.

The technology wasn’t isolating them, it was giving them a new way to be intimate (Douglas Rushkoff)

But despite that potential benefit, like South Korea, Rushkoff states “a sizeable number of American gamers also struggle with compulsive gaming” with one telling example of someone declaring that she gave up her job so that she could focus on playing World of Warcraft.

Chapter 7 of Digital Nation focused on Virtual Worlds.

Probably the most surprising example for me was the physical offices of Second Life where despite a completely open plan workplace Philip Rosedale the creator of Second Life often runs staff meetings around, say, virtual camp fires, using his own creation rather than face-to-face. He believes that people automatically behave better and with more empathy in virtual worlds in comparison to instant messaging or email. Indeed Rosedale himself only has desk in the open office but has much plusher virtual facilities. Rosedale believes that the problems of alienation caused by modern technology can be solved by better technologies such as he is trying to develop. Rushkoff asks viewers a difficult question however:

Do virtual worlds really bring us together with others or do they just make being utterly alone a little more bearable? (Douglas Rushkoff)

It’s not just Second Life’s Rosedale, however, who has opted for the virtual meetings route. This virtual worlds segment also highlighted how IBM is a major adopter of this as a solution and for good economic reasons (they saved $1 million in travel last year). But they also appear to be optimistic that this form of interaction is much more human oriented and is perceived as authentic interaction. Note also the impact on the use of physical space. Rushkoff visits a physical IBM facility built in the 1980s which was now mainly devoid of human presence because everyone was “out” and communicating “in” using technology. Indeed, one globally distributed IBM team had never met each other physically.

Chapter 8 of Digital Nation focused on whether Digital Experiences Change Us?

The answer seems to be, yes. The US military is a major researcher into virtual technologies, e.g. treating Post Traumtic Stress Disorder (PTSD) on the one hand and flying weaponised flying drones remotely. The change in behaviour in the latter relates to the detachment from physical consequence and the lack of personal physical risk. Unlike all prior experience a modern day virtual warrior who now may not even have flown a real aircraft before and is situated in the Nevada desert gets to go home for dinner with his family at night, i.e. “.. the disconnect between being at war and and home is very difficult for the human mind to wrap itself round“. That seems to be generating new variants of PTSD.

Chapter 9 of Digital Nation asks the question Where Are we Headed?

See the Army Experience Center in this segment and reflect on the form of this new style recruitment facility which is modelled on the Apple Store concept. Note also the reaction from anxious parents concerned that their children will be seduced by what is on offer.

But there are those who assert that our anxieties are generated by a generation who have no concept of the virtual whereas “kids have that ability to move seamlessley between the digital and the real” said Katie Salen of Quest to Learn who writes about the theory and design of video games and who founded a publicly funded school which uses video games as a lens through which to explore all aspects of the curriculum.

When kids are playing games they are engaging in a way that is incredibly similar to when they are engaged in reading a book. And that game world is equally rich I would argue to many novels. What is comes down to is that if you can’t engage a kid in wanting to learn something then you really have a problem on your hands. (Katie Salen, Quest to Learn)

Not everyone takes this view.

Schools are one of the few institutions in our society where you can have a sustained conversation about something without being bombarded and distracted by all these machines, we have to protect that. (Todd Oppenheimer, Author, The Flickering Mind)

But yet …

There were people who complained when we moved from horses to cars. There were people who complained when we moved from letters to the telephone. But it’s not that they are wrong totally. Things get lost . You might have less memory. Have less flowery writing. But we gain other things. And things move on. (Marc Prensky)

Technology challenges us to assert our human values which first of all means we have to figure out what they are … That’s not so easy … Techology isn’t good or bad. It’s powerful, and it’s complicated. Take advantage of what it can do. Learn what it can do But also ask what is it doing to us? We are slowly, slowly going to find our balance but I think it’s going to take time. (Sherry Turkle, MIT)

Digital technology continues to extend into every area of our lives. Yet the people developing these tools seem to be doing so with less regard for how we will be affected in the future than how we will be influenced in the present … I love the possibilities of a digital life. I love being able to experience the world through other people’s eyes. I love to be able to broadcast a story across the country from home, in my underpants … but most of all I love being able to turn it off. (Douglas Rushkoff)

When you have finished exploring the resources associated with Digital Nation and absorbed its multitasking message you can unitask over to the BBC/OU co-production site for The Virtual Revolution currently being broadcast on the UK BBC 2 channel on Saturday evenings and presented by academic journalist Aleks Krotoski.

The last 10 minutes of (or 50 minutes into) the first episode of Virtual Revolution with the title The Great Levelling? (note that question mark) offers a particularly powerful set of messages from the keynote contributors.

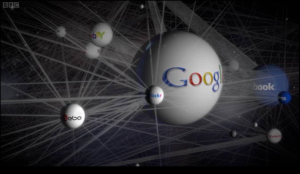

Those with the most resources can shout the loudest and impose their brands and their authority … This is a galaxy dominated by a handful of megabrands … The web has one search engine (Google), one marketplace (EBay), one bookshop (Amazon), and one social network (Facebook) that matter (Aleks Krotoski)

The massive aggregation of new wealth and power are the tiny elite of people from mainly Silcon Valley … You see in the internet a very pure manifestation of the way that power works, it lends itself to oligarchy, it lends itself to very narrow elites, and the internet is a perfect reflection of that. (Andrew Keen)

The concerns that I have are that there will be some sort of central control … in some countries it’s the government and in some countries it’s the companies, and I think that we have to be always vigilant about these threats or the whole web will become too frightening to use (Sir Tim Berners-Lee)

As a segue to her interview with Jimmy Wales the founder of Wikipedia Aleks Krotoski refered to the quality enhancement measures instituted by Wikipedia in response to the destructive or malicious impulses of some individuals who risked degradiing the value of the whole enterprise.

“Instead of truth emerging by consensus, increasingly it [Wikipedia] has to be policed” (Aleks Krotoski)

In this concluding comments to this first episode of Virtual Revolution Jimmy Wales himself stated:

“What I see happening is that communities can come together, create norms and standards and institutions for dealing with those things but it also involves drawing some lines and at some point saying you’re not being constructive and we don’t want you here” (Jimmy Wales).

The web has been colonised by new gatekeepers and new elites … and so the real question for me is whether the web is inherently unequal simply because it mirrors the inequalities and hierarchies in our world … For me the most important question about the web today is whether its idealistic beginnings have been relegated to history.I don’t think so because I believe the web is more than a simple reflection of our world. Instead it’s endlessly reinventing itself … Whenever one part of the web is closed down, colonised, and controlled, the technology opens up new frontiers. It’s a space of perpetual innovation … no one can stop it but we do need to take care of it (Aleks Krotoski)

And in his final contribution to the last minutes of the first episode of Virtual Revolution, Lee Siegel, controversial author of Against the Machine offers some final aurally quiet, but nevertheless conceptually loud, comments with his amplification message.

I think the web will really take on the contours of what culture has always been, there will be hierarchies, there will be elites. Like all technology the web is not a cure for human nature, it’s an amplification of human nature, both the good and the bad. (Lee Siegel)

Note that unlike the PBS Digital Nation production, the BBC/OU’s co-production Virtual Revolution is a series of four one hour programmes and I’ve only considered the first of those.

Final Comments

In conclusion, both of these programmes are potentially excellent digital resources that aim to be scholarly but at the same time try to be engaging works of general public interest. There is scope for some further enhancement however. The BBC/OU should learn from the chapterisation and user media wall facilities offered by the PBS Digital Nation; although the designers of the Digital Nation web site should draw greater attention to the chapter access facility; its just too easy to miss at the moment. The BBC/OU should also note how the US production team have made their signature documentary Digital Nation into part of a long-term project rather than just a series of interesting programmes.

Both public service broadcaster should normalise providing transcripts for resoures like these. Why? Simply because there is a lot of valuable commentary and potential citation in each production which will be lost because it’s trapped somewhere in the video stream. The older the programme becomes these information nuggets will become like insects trapped in amber – forever there, but just so inaccessible. I’ve tried my best to extract some of that commentary and potential citation but, boy, was it hard work.

Finally, I think that the Digital Nation video is a potentially valuable learning and teaching resource and so parts of it are certainly worth viewing several times, and so it’s a real pity there is, apparently, no download option as is provided for some productions by the BBC iPlayer. However, at least that may help encourage returners to the Digital Nation project site. But overall great stuff Fronline team and great stuff BBC/Open University.

Postscript (10 February 2010)

The four televison programmes making up the BBC/OU Virtual Revolution series has been re-edited into eleven 25 minute long programmes for radio. They are being transmitted on the BBC World Service starting 22 February 2010.

Academic journalist Aleks Kratoski who presents the Virtual Revolution has an article titled The challenges of filming the Virtual Revolution in Monday’s Guardian (8 February 2010). Aleks explains her vision for opening up the programme to influences broader than the production team and the keynote contributors.

And now here is a bit of “grit in the oyster”. I always find that Chris Woodhead, former UK Chief Inspector of Schools is a good source of controversy and polemic. Like most people I don’t always agree with him but I do respect his right to “rattle the bars of our mental cages” and here are a couple of extracts from his Sunday Times column “Answer the Question” which seems perfectly aligned to the topic of my posting. The first question was titled Shot down for taking computer games seriously (Sunday Times, 7 February 2010) which I replicate below.

Question

Cambridge University has set up a research and training centre for the study of children’s computer games, comics and picture books. The director, Professor Maria Nikolajeva, thinks that modern computer games offer children the chance to make moral decisions in a way they cannot when simply reading books. Do you agree?

Anne Matsuoka, Buckingham

Chris Woodhead’s answer

No, I do not agree with her. Cambridge University must have more money than sense. In that the printed page encourages the use of the imagination in a way a visual image never can, books have an enormous advantage over computer games and videos.

There is also the fact, if we are talking about young children, that the adult can read the story to the child and talk about it with them. It is the great classics of children’s literature that merit study, not contemporary computer trash.

Ouch!!! I wonder what he thinks of Digital Nation and Virtual Revolution? The pity in Chris Woodhead’s response is in his use of emotive language like “contemporary computer trash” he is expressing an extreme opinion whereas the work of a research centre would be to see if such strong opinions were actually justified or not. Chris, it seems, wants to eschew the trial phase and proceed straight to the public execution of anything that doesn’t align with what he is comfortable with. The assumption being that such investigations are of little merit and don’t merit any evidence gathering activity to either support or disprove his opinions. But there again, let’s not forget the purpose of a columnist is to be controversial.

The second question headlined Schools waste billions on white elephant gadgetry (Sunday Times, 14 February 2010)

Question

The Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF) spends £1.65 billion annually on IT for schools. What hard evidence is there that this makes any positive difference to pupil learning?

Nicola Baldwin, London

Chris Woodhead’s answer

None whatsoever. IT can and, when used properly, does help teachers teach and pupils learn. Often, of course, it is not used properly, and often, as Armando Di-Finizio, the head of Brunel academy in Bristol, said recently, it doesn’t even work. In his view the current obsession with updating technology has resulted in millions of pounds being wasted on “white elephant†gadgetry. I agree. Last year ministers announced that all primary schools must provide “learning opportunities†through the effective use of technology. Personally, I would rather see teachers free to teach as they see fit, inspiring children with their own passion for their subject. Our cash-strapped government could save £1.65 billion and as a consequence raise educational standards.

We may agree or disagree with his viewpoint but gathering that evidence is going to become increasingly important if voices like his are not to get louder and louder.

“Both public service broadcasters should normalise providing transcripts for resources like these. Why?â€

I’d like to add an additional reason.

It’s not simply because “there is a lot of valuable commentary and potential citation in each production†but because those who are digitally excluded from the Virtual Revolution in the first place, through lack of inclusive design and affordable assistive technology, are those with the most to gain from alternative modes of access. I’ve watched two episodes of the BBC programme and have yet to see any mention of the ‘revolutionary’ ability of digital data to be customized to suit individual need and preference.

Sue

[…] anyone wanting to delve into this a bit more deeply may find this and another posting of interest (Are you digital natives paying attention?, Auricle, 6 February 2010) and Technology Impeded Learning, Auricle, 29 September […]

[…] anyone wanting to delve into this a bit more deeply may find this and another posting of interest (Are you digital natives paying attention?, Auricle, 6 February 2010) and Technology Impeded Learning, Auricle, 29 September […]