by Derek Morrison, 20 May 2010

Any views expressed in this online essay are those of the author alone and should not be construed as necessarily representing the view of any other individuals or organisations.

Today’s posting is an addition to my de facto segue on ebooks, words and techno-anxiety a topic I’ve addressed at different levels in Same as it ever was (Auricle, 21 March 2010), No Country for Old Readers (Auricle, 28 February 2010), and Ebooks what ebooks? (Auricle, 21 February, updated 24 February).

The growing presence of mobile devices like smartphones and ebook readers reminds me of my deliberations about the impact of MLE/VLEs way back in 2004 when I first launched this iteration of Auricle as a blog. In summary, my concerns expressed at the time was that Higher Education had allowed itself to become locked into an immature and, at the time, invariably proprietary construct of what a Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) or more accurately a Managed Learning Environment (MLE) – alias Learning Management System (LMS) should be. Wind forward to 2010 and I find myself interested in whether mobile devices and portable e-readers have the rather confusing potential to either disrupt or reinforce the LMS concept. Or indeed in some cases to become a key facet of an ever evolving online learning environment. But why would this be the case?

Whose fuel, whose vehicle, whose supply route?

I introduced the concept of e-learning “filling stations” in a series of earlier articles, e.g. eBooks and the e-learning ‘filling station’ revisited (Auricle, 25 September 2008, updated 26 September 2008 and 19 February 2009). In this series of earlier articles I used a transport infrastructure metaphor to project the idea of a broad range of learning ‘vehicles’ able to be ‘refuelled’ at whatever ‘filling stations’ on the ‘road’ the driver of the vehicle chose rather than being tethered to particular stations dictated by their ‘vehicle’ manufacturer. Consequently, it seems pretty obvious to me that the moment has now arrived when we need to be carefully assessing the impacts of a learning environment in which key aspects of the digital ‘fuel’ for learning and teaching risks becoming locked into a limited number of supply and delivery chains. To stretch the metaphor just a little more, the risk arises from a small number of key actors ending up controlling fuel extraction/generation, fuel delivery, the roads to travel, and even the vehicles in which we travel. Both the smartphone and ebook reader with their wireless internet connectivity already offer their own fine examples of this supply chain control whilst simultaneously being presented to buyers/users as vehicles for establishing a more personal environment. To date, the simplest of ‘fuel’ to understand has been the book, that aggregation of words, that conveyer of information, knowledge, narrative, and culture. But as the pace of its digital transformation quickens that simple aggregation of words is adopting the mantle of the enhanced book or even the awful but memorable ‘vook’, i.e digital books plus video and internet enhancements, e.g. social network connections. For one nascent example, of such enhancements owners of iPhones might wish to download Hilary Mantel’s Man Booker 2009 winning Wolf Hall from the iTunes Store (there is also a free sample version for those just wanting to grasp one publisher’s view of what an enhanced edition actually is). Publishers like Simon and Schuster are also now in the ‘vook’ business. To this potent technological and business model redevelopment mix come devices like the iPad (or its descendants or wanabees) which are are also multifaceted ebook devices but ones which are tethered to one supply route or another.

But whose supply route will it be? Sticking with the ebook as representative of one type of ‘fuel’ where are we going to be getting our books from in the future? A bookstore? A library? iPrincetonU? iOxfordU? iCambridgeU? iPoppletonU? Or will it be iTunesU or iAmazonU, or even iCloudU?

Here are a few ‘alternative’ supply routes to reflect upon:

- The Internet Archive’s BookServer service. I downloaded Lawerence Lessig’s 2008 classic Remix: making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy from this useful source. While the Internet Archive’s search interface needs further work it’s services such as this one that point to the future of ebook publishing. Note also that Cornell University is partnering with the Internet Archive.

- App Store Now Has 150,000 Apps. Great News For The iPad: Paid Books Rule (TechCrunch, 12 Feb 2010) stated:

… the highest percentage of apps in the App Store are now paid book applications. In total, there are over 27,000 book apps in the store, and of those 92% are paid apps, according to Distimo’s data. - Books Outnumber Games on the App Store (Mobclix, 1 March 2010). See also the MobClix dynamic chart for up-to-date information.

- Feedbook.com enables users to create own “newspaper” from aggregated RSS feeds and download it as an ePub, PDF etc

- Lulu the print on demand/self-publishing service now offers ebook publishing as well as print forms. Lulu also contends that:

70% of our authors make their print books available as downloads, and those authors sell 30% more books than those who offer print editions only … Why publish an eBook? The simple answer is it makes sense for both authors (universal distribution, more sales, and higher royalties) and readers (cheaper than print, instant delivery, and mobile access).

Interestingly, despite the positive outcome for author sales, the Lulu statement above was based on PDF format ‘ebooks’; a less than ideal ebook format which is more suited to workstations and laptops. Lulu now also support the open ePub format a non-proprietary format much better suited to portable ereader devices.

- Google started offering public domain ebooks in the ePub format in 2009 (select subject and then public domain from the Google Books site). It’s worth noting that the scope and scale of Google’s ebook ‘production’ process depends on the scanning of physical books and then conversion via optical character recognition (OCR) software. Despite considerable improvements to OCR over many years the conversion process is not 100% reliable. The introduction of some errors is, therefore, inevitable

- Academic publishers like Blackwell’s have now made a serious entry into the ebook world with some 45,000 titles which use the ePub format but some of the prices are, well, to say the least frightening and don’t reflect the lower publishing and distribution costs

.

“Buy-in” to still evolving open standards like ePub for ebooks is important unless we are to end up in a situation analogous to a car which will only run on fuel that can only be purchased from one brand of filling station; a situation which (conveniently ignoring environmental considerations) would, to understate the case, not meet the expectations of modern highly mobile societies who expect to be able to drive almost anywhere and refuel almost anywhere in the world.

ePub is similar to IMS or SCORM learning objects in that the book (the object) is actually a package of files and metadata about the files. Because the package has a standardized format that means that reader applications and systems can manage and display the book. In essence an ePub file is just simply a renamed zip file with a bunch of metadata and XHTML files and that is why by building on existing solutions first developed for the web the content reflows no matter the screen size of the device it is displayed on. Consequently, just like a web browser page whatever ereader device or software an ePub file is opened in it should readjust for that format making it an ideal format for mobile devices. We should note, however, that there are two forms of ePub, one incorporating Digital Rights Management (DRM) and the other free of DRM but at least this open format is facilitating the development of a single industry standard. Even major ebook players like Sony are now adopting this open standard despite orignally entering the market with their own proprietary format. Amazon, however, still persists with their own brand of ‘fuel’ and would prefer to sell you their particular brand of car (as manifested by the Kindle) or, more recently, some software variant of their car so that they can maintain their supply chain for just a little longer.

But as I’ve previously discussed in Ebooks what ebooks? (Auricle, 21 February, updated 24 February) the definition of an ebook is broad and many organisations conveniently (too conveniently in my view) include PDF files read on a workstation or laptop connected to a network in what they communicate as being an ‘ebook’. I think that the now near ubiquity of wireless mobile devices should force us to reflect on what we label as an ebook. The analogue book was a towering technological success because it was convenient, information dense, self-contained, highly portable, and robust. It’s kind of hard for me, therefore, to construe entities that are tethered to a network, not portable, and not self contained as ebooks just because they are displayed on a workstation or laptop. Try reading them on most planes or trains. I suggest that user behaviours when interacting with rapid access untethered portable devices cannot not be equated with how they will behave when interacting with less portable devices that have to be connected to a network to function as ‘ebooks’. As a slight aside Auricle readers wishing to consider how mobile technologies are impacting upon strategic thinking may be interested in the Educause ~11 minute podcast Seton Hall’s Mobile Initiative.

PDF has an important place as a portable document format but its paper-oriented heritage shows and I think it is, currently, a very poor contender in the ebook format ring; particularly in its image variant as anyone as anyone who has struggled with reading a PDF on a small mobile device will testify. Digital document formats need to automatically reflow to suit different display devices but in PDF this capability needs to be first activated by authors and then translated by whatever PDF reading software is being used and, unlike XHTML readers (online or offline browsers) that capability cannot be assumed. Also from my own experience, converting PDF to more flexible formats like ePub produces unsatisfactory results. Those wishing to explore further some of the accessibility issues related to ebook formats may find the TechDis article e-Books and Accessibility – a briefing for education libraries of some interest. We also perhaps need to reflect rather more deeply than we are that the majority of users will be prepared to sit in front of a workstation or laptop display for protracted periods to study an ebook – I suggest that they won’t, they will browse, cut and paste or maybe print what they need, and get out; a factor, I suggest, that needs to be considered when considering the deliberations of the 2008 CIBER study the Information Behaviour of the Researcher of the Future (PDF), a study I’ll consider again later in this essay. Google’s recent announcement of its forthcoming Google Editions ebook service should also be of some interest. We can but hope that the statement “Google Editions would be able to read books from a web browser—meaning that the type of e-reader device wouldn’t matter.” (Google Readies Its E-Book Plan, Bringing in a New Sales Approach, Wall Street Journal, 4 May 2010) doesn’t translate into ebooks that can only be read from a network-connected workstation or laptop but actually means that Google will embrace a standard like ePub with download and reflow capabilities for ereader devices with content that can also be read offline.

It currently seems to me that while development of ePub has some way to go it is probably the easiest and most accessible solution because of its XHTML foundations and so will enable most interested authors to dip their toes the ebook waters. A great source of general information about all things ePub is the O’Reilly Labs’ EPUB Resources and Guides.

What do we mean by an ebook anyway?

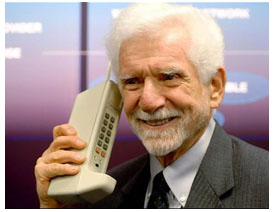

Our conceptions of what an ebook is are likely to change.  In the early 1970s how the passengers on a bus I was travelling in laughed when another young man plugged a set of headphones into what then passed for a ‘portable’ device – a cassette tape recorder. Also, how we smiled at what was then viewed as the slightly ridiculous sight of the early mobile phone users with ‘bricks’ glued to their ears – such early adopters thought it was just envy really. But we don’t laugh now at headphones or mobile phone in this age of iTunes, iPhone, iPods, and now iPads – although the last has provided a ready source of visual humour disseminated widely on the web

In the early 1970s how the passengers on a bus I was travelling in laughed when another young man plugged a set of headphones into what then passed for a ‘portable’ device – a cassette tape recorder. Also, how we smiled at what was then viewed as the slightly ridiculous sight of the early mobile phone users with ‘bricks’ glued to their ears – such early adopters thought it was just envy really. But we don’t laugh now at headphones or mobile phone in this age of iTunes, iPhone, iPods, and now iPads – although the last has provided a ready source of visual humour disseminated widely on the web

But despite the opportunities for contrived or retrospective humour there is a serious point to be made here about the suitability of different devices for accessing the web, the ‘fuel’ the web offers, and the conclusions that we may be tempted to draw about the explanations for the behaviours we exhibit when using them in different contexts. We should not confuse iPhone, Google Phones, iPad, ereaders etc with laptop or desktop computers. Some of these have a different purpose. Some devices are primarily suited to consumption, i.e. reading, viewing, listening devices with constrained but useful forms of interaction, e.g voice calls, texting, short emails, image/article email forwarding etc. If we do confuse our access devices then we also risk confusing students by trying to use inappropriate devices for inappropriate pedagogical purposes, e.g. it’s not reasonable to expect long form writing on a consumption device; although voice notes etc on smartphones may contribute to such work on other, more suitable, devices.

While the focus of this posting is meant to be the ebook I also think there is something to be learned from viewing some of the emerging online examples of digital magazines particularly for the current “king of the hill” the Apple iPad, e.g. Wired. Or view the paidContent:UK blog article Cool-Seeking Newspapers Dream Of iPad (12 March 2010). Or read How will print content look on the iPad? (Guardian, 12 March 2010).

So what’s the relevance of the development work the emagazine visionaries are undertaking? Despite my recognition of the importance and the unmatchable efficiency of words for vectoring knowledge and information, ebooks are inevitably being viewed as providing something richer than just textual narrative. The concept now if of the “enhanced” ebook, although most current forms are rather conservative, typically a web site linked to the paper publication which adds further value, e.g. author interviews etc. But a properly specified portable/moble ebook reader could these enhanced elements in the actual ebook, much like a DVD has it’s “director’s cuts’. Other devices are going this web integrated route where external services are aggregated around a focused theme or ‘information object’ , e.g. a recorded television programme – see Internet TV: the goggle box gets googly (Sunday Times, 7 March 2010).

But there is also the much more media integrated entity some call the”Vook”, a concept highlighted in Ebooks: Getting Beyond Disruption (Ania Wieckowski, Harvard Business Review, 26 February 2010). And as Alice for the iPad shows the very concept of what it means to interact with a book is now being expanded (although I would personally be very nervous about handing over an expensive and fragile device to the age group that would enjoy such interactions with this particular ‘ebook’).

As I highlighted in my No Country for Old Readers? (Auricle, 28 February 2010) Negroponte reminds us that words are very efficient carriers of knowledge and information in a relatively small space. But a large proportion of the human brain is dedicated to image processing, albeit at an unconscious level. There is much written about this but a very accessible illustration of the power of visual processing and visual memory has been undertaken by the well known author and academic Richard Wiseman. For example Wiseman states in his book Quirkology “We don’t process verbal information anything like as efficiently, [as images] so associating names and lists with images is probably a good strategy.†The Quirkology web site also shows the live Total Recall experiment he ran to replicate the original studies undertaken by Lionel Standing in the 1970s. See also Think your memory is poor? Forget it (Times, 19 May 2007) or the VizThink blog.

And what about the graphic novel or comic in this fast evolving ebook world? I downloaded Wallace & Gromit: The W Files, one of the free books on the Apple iTunes store, not because I’m a fan but I was interested in the experience of a story being narrated primarily via graphics using a mobile device. Although the Wallace & Grommit example was a comic it had, nevertheless, some interesting lessons to offer if applied to the development of any graphics rich learning object, e.g. some ‘frames’ contain an navigation hotspot enabling readers to digress from the linear graphical storyline to receive contextual information.

So maybe the Vook concept is worth considering for that reason but also the concept of media enhanced books surely has myriad of applications in learning in all disciplines? There are questions of course about not interrupting narrative flow but that is perhaps less of an issue in areas where the association of text with the ability to visualise or listen to the object under discussion would enhance associative learning without disrupting the overall linear narrative. In fact an inline hyperlink could well represent a greater disrupter of narrative flow. The challenge here is to ensure that the hyperlink or media item does not break the narrative flow but contributes to it. In which case this online essay is a negative exemplar of disruption of narrative flow. In my defence, however, I suggest reading digital formats efficiently requires that we develop the ability to inhibit our desire to explore every single hyperlinked route or byway until we have followed the narrative of the host resource, i.e. we read something more than once with different iterations serving different purposes; an argument I know that is counter to the “browse and jump” ethos so easily developed when using web tools but which should surely be part of our advocacy of developing digital and – or – scholarly literacies? However, those interested in exploring the issues relating to the placement of hyperlinks in ebooks may be interested in the O’Reilly Tools of Change resource Publisher Offers Tips for Embedding Web Links in Ebooks (Mac Slocum, TOC, 2008).

But we cannot consider ebooks without also considering ebook readers. At its most basic level the ebook reader can manifest as a very simple portable computer device complete with an local web browser implementation that can intermittently connect to a server and download files for offline reading. As indicated earlier these ebook files can easily be packaged in standardised XHTML format plus metadata called ePub. That intermittent server connection is a fundamentally simple but crucial part of some ebook business models because it is here that access can be restricted and so profits can be made. It’s ironical, therefore, that standard web browsing from what is after all a simple computer can be somewhat challenging or is presented as a ‘killer’ feature in an ebook. The Amazon Kindle particularly in the UK context provides an interesting case study in this regard. Because Amazon uses mobile telephone technology for server access it can restrict this to intermittent file downloads and may not be prepared to activate general web browsing in all countries, including the UK. Open web access would require the Amazon data download service to be based on an “all you can eat” arrangement and that is dependent on whatever regional telecom arrangements they can make and Amazon’s willingness to either absorb the costs or minimise the impact on their ebook prices. As they are in the ebooks business and not the internet service provision business they have a dilemma. eBook readers that offer wi-fi solutions should be less problematic in this regard but of course this is more ‘tethered’ than the mobile phone technology solution which conveys the impression of always available access. Caution needs to be exercised, however, when taking such a telecom linked device outside of the country where the telecom agreement applies else unexpectedly high out-of-country data charges may also become a factor to consider. In the telcoms world the global village can be smaller than we think.

A really useful ebook reader would, however, not just be a consumption device, it would allow for emailable/sharable margin notes and contextual annotations (preferably by scripting) and web browsing and whatever. But one of the great ironies about ebook readers is that the best examples will also facilitate writing – natural note taking for the equivalent of margin notes. Annotations by keyboard particularly a screen keyboard are just too much trouble. Handwriting recognition would be nice but is not essential whereas being able to email handwritten comments with a ebook reference would be neat. The most expensive crop of the current readers currently show what can be done, e.g. iRex. So just as the best examples of blog authoring are facilitated by extensive ‘reading’ the best examples of ebooks may well be facilitated by extensive ‘writing’ facilities and features. As I said, ironical.

A changing role for authors, readers and publishers?

There are some who argue that the ebook is a disruptor of the traditional separation of author and reader roles. That’s an aspect referred to in Books 2.0 one of the items in the On the Media special the Past Present and Future of the Book (On the Media, 27 November 2009). The On the Media item highlights the views of Bob Stein a member of the US think tank the Institute for the Future of the Book whose blog essay A Clean Well-Lighted Place for Books informs his OTM interview. The changing nature of what is means to be an author (or a publisher) was also addressed in Sara Lloyd’s A Book Publisher’s Manifesto for the 21st century available either as a PDF or, as I read it, in the form of a chapter in the free Best of TOC ebook (ePub format of course) which is downloadable from the O’Reilly site.

But not all authors are happy.

Here’s an extract from one author’s view of the ebook and its impact on the reading experience.

Technologies are not neutral. They come with a bias. Not a political bias — a narrative bias. A news story broadcast on television, an acutely visual medium, is different from the same story published in a newspaper or broadcast on radio. Form is function. Someone reading a book on a Kindle has a fundamentally different experience from someone reading the same book the old-fashioned way.

(Source: Eric Weiner, In An Era Of Immediacy, Why Fear The E-Book?, NPR’s All Things Considered, 27 January 2010, N.B. 3min 58sec podcast and transcript).

And what about the role of the tradtional publisher in a world where the internet facilitates disintermediation and so disrupts existing business models? There is some scope, therefore, for a new type of publishing in which authors may be tempted to go it alone or form their own co-operatives and so can reach directly out to their audiences without the publisher intermediary. A world where universities or groups may choose to publish their own works because they perceive the publisher not to be adding sufficient value. For example, see Who Needs You, Big Publishing? How Authors Can Own All Rights and Make More Money (Scott Sigler, 24 February 2010, TOC Conference 2010). Authors can now also publish via institutional or institutional consortia using offerings like EPrints or DSpace. Both alternative software engines of a growing number of institutional scholarly repositories that are becoming part of the infrastructure of the Open Access movement. JISC’s leadership role in promoting an open access ethos in the UK should be noted (JISC, 25 February 2010). As is increasingly the case, however, the internet can disrupt established business models and processes and so the concept of open access has become a source of some concern to the traditional academic publishers (STM, 16 April 2010). Educause also offers us a useful ~7 minute podcast about Open Access Policies at Harvard generated from an interview with Harvard’s Sue Kriegsman at the 2010 Spring Membership Meeting of the Coalition for Networked Information (CNI).

The role of the traditonal publishers is further disrupted by the presence of the super-distributors such as Amazon and Apple who develop and exploit online technologies by providing online services, e.g. iTunes in the case of Apple that can deliver a variety of content directly to media devices, including ebooks. One particularly proactive and innovative tradtional publisher in the ebook arena is O’Reilly who seem prepared to experiment with different business and technical models. For example, their Bookworm service offers an interesting alternative easy to use example of how to books can be downloaded to mobile devices like the iPhone. Bookworm is an implementation of the Open Publication Distribution System (OPDS) which is “… intended to enable content creators and distributors to distribute digital books via a simple catalog format“.

But if authors, readers and publishers are faced with the need to adapt to the new opportuntities and challenges posed by the ebook how are those most public of the institutions built around the products of dead trees, i.e. the libraries, adapting? An aspect we will consider in the next section.

The ebook and the public library?

In the ever evolving digital world the process of change is already underway that currently looks like it will make the idea of making a journey to a particular building in a particular city or town just to acquire a resource that could easily be remotely downloaded in seconds or minutes directly to a reader or player device a rather quaint Victorian practice. Of course public libraries are not standing still and have recast themselves as important access and advice centres in their own right but even their shelves of videos, audiobooks and DVDs now look somewhat dated in comparison to the bits and bytes that can be transferred and reassembled from a variety of sources – not necessarily from within even the boundaries of one country never mind a single library district. The recent Guardian article The battle of Britain’s libraries (Guardian, 7 March 2010) provides a useful reflection on the issues and how public libraries are attempting to respond to them. But whatever fate awaits them how are public libraries responding to the current ebook opportunties and challenges? It would perhaps be useful to roll the clock back five years and consider the 2005 UKOLN article Ebooks in UK Public Libraries: where we are now and the way ahead. The UKOLN article highlights the importance of the library not becoming trapped in an unwinnable technological arms race and so comes down on the side of perceiving the ebook as software; hence highlighting again the importance of ebook standards. But if I borrow a dead tree derived book from my local library I get to keep it take it away for a set period. How can this be achieved in the digital world?

One approach to the digital ‘loan’ is provided in this extract from the Finding Free eBooks blog:

If your local library doesn’t have ebooks, look for a large city that is close to you. They may have ebooks available to check out … You will need the ability to read drm’d versions of these formats to read a library book. You will be able to check out the book, from home via the internet, for a specific number of days, which varies from library to library. Some places let you choose the number of days you keep the book. After the time has expired, the book will no longer open. This assures only one person is reading the book at a time. You may have to wait to check one out if it’s already being used.

The above is similar to the process employed by the non-streaming variant of the BBC iPlayer whose video downloads will cease to function after a specified elapsed time.

In US the Overdrive company appears to be a key player in the above ebook distributions but they do describe themselves as a global company so using Overdrive Digital Media Locater provides some useful insights into public library penetration of this portable ebook download model throughout the world. For example, in the UK Liverpool Libraries offer such a download service. Unfortunately, my sense of admiration was tempered somewhat by the realisation that the download must be played in the Adobe Digital Editions player thus effectively tying the reader to particular devices and obviating the key benefit of using an open standard, i.e. it should be the ePub standard not the Adobe® EPUB standard. However, the Overdrive ebook videos are a relevation we could all learn from and gives a sense of a possible future for all libraries. Note Adobe EPUB can be read by the Sony Reader because it uses Adobe Digital Editions, so you can copy the download from PC to the Reader.

It’s interesting, given the emphasis of the 2005 UKOLN paper mentioned earlier, and the now more dynamic nature of the ereader market, that a publicly-funded body like the British Library appears to have eschewed adopting a platform agnostic approach. It appears to have pinned its flag to the Amazon and Kindle mast, i.e. read A new global readership for forgotten literary gems (Dame Lynne Brindley, 7 February 2010). In her newspaper article Dame Brindley states:

Making 19th century fiction available for free through the Kindle ebook reader opens up a new global readership for forgotten literary gems. Kindle users will be able to download, free of charge, 25m pages of digitised books, from noteworthy editions of well known authors like Dickens, Conan Doyle and Thomas Hardy to rare early 19th century fiction and even the UK’s best collection of ‘penny dreadfuls’. People who want their own copies can also have them despatched direct through Amazon’s print-on-demand service.

Amazon has not yet embraced open standards but instead has opted to offer its own free ereader software for reading books purchased for the Kindle device on a range of other platforms. There is, for example, a Kindle app for the iPhone but I find it to be a stark reading experience in comparison to the equally free Stanza ereader offering (ironically developed by Lexcycle, a company acquired by Amazon in 2009). From one perspective such apparently platform and distribution network specific decisions by the British Library firmly ties readers to the offerings provided by the Amazon store, thus linking the institution with and promoting a single e-trader/e-distributor network; while also apparently eschewing open standards like ePub. From another perspective, the British Library wants to achieve as much reach as possible for the initiative and at the time the decision was made I assume they construed Amazon as the dominant player in the ebook space. It is certainly both an interesting and courageous policy decision in what is after all fast evolving ebook landscape with new incumbents like Apple also wishing to have a major presence in this space. Other channels and formats may, of course, also be under consideration but Dame Brindley’s article provides no information about this.

The ebook and the academic library?

So is HE a hotbed of ebook innovation? Are academic libraries doing anything different from the public libraries?

Some academic libraries are apparently making part of their collections available in ePub format, e.g. the NZ Electronic Text Centre (part of Victoria University Library).

Arguably, some useful information about ebook policy decisions can be gleaned from examining what format dominates in, say, EPrints archives, it appears to be PDF. DSpace archives show much the same picture. Although at least Behavioural and Brain Sciences archive offers their outputs as HTML.

So what are our publicly funded government and HE agencies doing in this regard? See JISC launches first e-book (JISC 2 March 2009) which is showcasing a PDF format ebook. See also the JISC Ebooks for FE Project and a complaint from a user with expectations that the ebooks will display on their particular mobile device (Nintendo DSI).

In several of my previous articles I’ve highlighted the JISC National E-Books Observatory Project (PDF). More specifically, however, I have indicated in my Ebooks what ebooks? (Auricle, 21 February 2010) article that the JISC National E-Books Observatory Project has to-date adopted a specific internet connected, library-oriented, and walled garden ebook construct that is somewhat removed from a world of mobile e-readers in which content is downloaded for offline reading at the individual’s leisure. I think we cannot assume, therefore, that the behaviours of those engaging in the internet session-based model of the Observatory projects (where it’s possible to undertake deep log analysis) are generalisable to all ebook forms or whether such behaviours are a consequence of the internet session oriented model of the ‘ebook’. We need to recognise, however, that the UCL CIBER team walled garden studies have generated some very helpful insights in the context of the environment they analysed. Repeating such studies on personal/mobile e-reader devices would be considerably more challenging from a research design, technical, and ethical perspective. For example, let’s say a research team produce a monitoring app for smartphones and other ebook readers that would enable the equivalent of the CIBER deep log studies in this new context. But then there is technical development effort and expense of producing several variants for different smartphones and devices, e.g. one for the Amazon Kindle, one for the Sony reader. But manufactures of such proprietary devices may not be keen to allow such monitoring on their platforms. Then volunteers would be invited to take part. But are the volunteers representative of the general population and will their behaviours actually be changed by such a study? I supposed it’s possible to conceive of a double blind study in which a population under study could download a monitoring app with 50% of the apps being active and 50% being inactive with neither half of the cohort knowing which they had. Again such a research design would be, to say the least, “challenging” because it be the equivalent of fitting a bugging device to a phone.

The above contextual factors are acknowledged by CIBER’ Director David Nicholas’ comments in the online item Ebooks are here to stay (Research Information, April/May 2008).

‘No one is doing any serious reading at all online,’ he said. Users are engaging in ‘power browsing’, he continued, with sessions lasting only three and a half minutes on average, with a relatively short time spent on any single site. Users spent as much time searching as viewing the content.

The Research Information article goes on to say:

OCLC has made similar observations on its platform. According to Wasinger, the average session time for users is 15 minutes, while the average time per book is 8.5 minutes. ‘This tells us that users go in, use the platform to perform a very specific search, find exactly the book and section that they need, copy and paste it or take notes then get out,’ he said.

And so in considering the CIBER studies about the online behaviour of library users I think we have to remember that that this behaviour is not active reading behaviour. It is, instead, highly targeted acquisition behaviour perhaps modulated by the interfaces and infrastructure the ‘searchers’ are connected to. That, to me, does not necessarily translate into ebook reading behaviour using an untethered portable device; but the knowledge base in this more mobile context is, as indicated earlier, less amenable to the deep-log analysis possible when tethered to a server and an underlying network infrastructure.

But no reflection on ebooks and academic libraries can escape considerations of the future of textbooks and journals in a digital world. But that would merit a posting of its own. So to escape this I highlight the TOC 2010 conference where there was a session titled The Future of Digital Textbooks which was preceded by most interesting online panel discussion.

Conclusion

Despite the undoubted growing traction of the ebook concept I still find it hard to accept that any single function text delivery device will emerge as the ultimate ebook platform in a world where the very concepts of what is a book?, what is a bookshop?, what is a library?, and what is reading? are being disrupted. At the moment what is being sold is the idea of the exciting new ‘ebook’ but in reality dedicated ebook readers are no more than simple constrained-function computers plus a viewing application which, in combination, can control both the access channels to, and format of, what are relatively simple content files.

In a world of increasingly rich, integrated and connected content, however, the sustainability of continuing to charge a premium price for constrained function hardware and textual content just by calling it an ereader will become ever more questionnable. To compete rich content ereaders will need to remove the constraints and so become more explicitly computer like in their ability to integrate text, audio, video and hyperlinking to the wider web at which point the ‘ebook’ function becomes but one of their capabilities. For this reason I find it bizarre in the extreme that currently the provision of a web browser in one or other premium-priced ebook platform is either trumpeted as a either major feature, downplayed as experimental, or alternatively, is entirely inhibited in some regions. In the original series of Star Trek the emotionally constrained character Spock had what appeared to be a magic ereader type device which could apparently access whatever multimedia information he needed – one incidentally which never seemed to need recharging. I suggest that Spock would not have been happy with some of the devices posing as ereaders at the moment although he may have glanced with a flicker of interest at more media capable tablet devices like the iPad or its design descendants.

As ereaders, evolve, however they could become the ultimate Spock machine both for streaming and pulling down the bit of the web we need at the time for temporary or permanent storage, or for transfer to other devices. From bitter personal experience of mobile and remote access, I’m currently unconvinced about a digital world where the ‘cloud’ plus data streaming will meet all needs – much of the national and global infrastructure is just not robust, flexible and accessible enough. Plus data access/download business models seem designed to be a positive disincentive to building confidence in such a future. But, as the uptake of smartphones and other mobile access platforms has shown, there is a large demand for well designed gateway physical devices which users can use to acess the rich information, services, professional and social contacts that matter to them and the various contexts that frame their lives. And so it is here that we should be paying much more attention when we consider what an engaging and meaningful reading experience could, should, or now needs to be; rather than focusing on what have been no more than expensive first generation devices that, in the main, mimic what we already do with dead tree based media. Such mimicry still has a place but as part of a much richer, easy to use, and affordable gateway device than is currently being offered under the ebook/ereader banner. The Apple iPad and Plastic Logic’s QUE perhaps offer a glimpse of what such gateway devices could be albeit the former uses LCD display technology (a light transmissive approach more suited to multimedia) and the latter uses EInk (mimics some of the light reflective qualities of paper and so is intended to decrease reader fatigue but is currently not suited to multimedia). Plus smartphone developments continue to plough their own disruptive furrows.

So the question is whether dedicated ebook readers are really what we need at all or whether ‘ebookery’ is best realised in software integrated into highly portable/usable, rich media and network capable quick starting devices – a construct that even Amazon with its Kindle software now appears to be embracing. Ironically, the invention of EInk display technology has contributed to this divergence in how ebooks can be realised. EInk devices offer attractive affordances in being good at displaying readable text and maximising battery life but they also constrain, i.e. are poor on colour and the rapid display updating necessary for video. My money is on convergent solutions in the long term with users being prepared to trade some quality in one dimension for flexibility in the others.

Further reading, searching, or listening

- Search the Intute service with term “e-book”.

- Search ERIC (Education Resurces Information Center) with terms “ebook” or “e-book”.

- An Investigation into Free eBooks (AHDS, 2004)

- Books in the age of the iPad (CraigMod, March 2010)

- 30 Benefits of Ebooks (EPublishers Weekly, 28 January 2008)

- Educause podcast The E-Textbook Conundrum (10 December 2009)

- Educause podcast Digital Histories for the Digital Age – How Do We Teach Writing Now? (12 February 2010)

- Educause e-book resources including E-Books in Higher Education: Nearing the End of the Era of Hype? (EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 43, no. 2, March/April 2008).

- Electronic Publishing is another high value Educause resources category. As is E-Readers and E-Textbooks and Handheld and Mobile Computing.

- Educause’s ebook collection (html, pdf). Comment – It’s a pity that Educause as a leading organisation does not offer the ePub format.

- The Global Text Project (although initially prepared in Open Document Format (ODF) the ‘ebook’ offerings mostly appear to be recast into PDF with some exceptions)