by Derek Morrison, 28 February 2010

Any views expressed in this online essay are those of the author alone and should not be construed as necessarily representing the view of any other individuals or organisations.

My apologies to the Coen brothers for the abuse of their No Country for Old Men. In this posting I am attempting to extend and merge the themes addressed in two earlier postings. First, Are you digital natives paying attention? (Auricle 6 February 2010) and Ebooks what ebooks? (Auricle, 21 February, updated 24 February). The conceptual mashup constituents are attention, reading, words, books and ebooks.

The fourth and final part of the BBC/OU production of Virtual Revolution was titled Homo Interneticus and as with previous episodes I found it presented a fairly balanced case that explored the affordances, constraints, and emerging issues relating to the web. The big question in this episode was what the internet may be doing to our behaviour and even our brains. I’ve included the time codes for where I think the real gems lay in this edition of the programme. (~32:00) A focus on Vannevar Bush’s seminal article As we may think (Atlantic Monthly, July 1945) which first posited the benefits of associative as opposed to linear thinking realised through a vision of liberated minds accessing a vast library of human knowledge which would be open to all. The presumption here was that technologies would eventually free us from constraints of linear thinking and facilitate a more natural associative thinking. Of course Tim Berners-Lee’s catalysis of the world wide web some 20 years ago led to our present day realisation. The question posed by Aleks Krotowsky in Homo Interneticus was whether the ability to leap from one piece of information to another is always a good thing? Ironically, the contribution which followed was also in the Atlantic Monthly albeit some 63 years later than Vannevar Bush’s. Nick Carr (Author, Is Google Making us Stupid?, Atlantic Monthly, July 2008) was asserting that science shows us that the human brain likes to be distracted and so:“because the web bombards us with stimuli it plays to that aspect our our brains … it keeps our brain hopping and jumping and unable to concentrate.”

And Clay Shirky poses the question:

“When you grow up expecting to find information at a moments notice what does it do to your ability to internalise information?”

Aleks Krotoski then links with:

We used to be trained in the discipline of reading and writing at length. But now the generation of the web’s associative links seem unable to face the rigours of such linear thinking … even, in turns out, at our top universities (Aleks Krotowski)

To back up this assertion Aleks brings forward David Runciman, Political Scientist, University of Cambridge who states:

(36:53) What I notice about students when I see them at the first day at university is that they ask nervously, what do we have to read? And when they are told that the first thing they have to read is a book, they all now groan. Which they didn’t used to do five or ten years ago. And when you say why are you groaning? They say it’s a book, how long is it? … (37:28) I still think that books are at the heart of what it means to be educated and to try and educate and I think the generation of student that I teach see books as peripheral.

That contribution is followed by David Nicholas, Director of CIBER at UCL who states:

(37:12) Just take you own doctor. Would you be happy if your own doctor simply skimmed the abstracts of the Lancet and all the major databases and never read anything in detail. How happy would you be?

(38:04) But Aleks Krotosky does address the question of whether this is just the grumblings of an older generation and offers an example of an attempt to gather evidence that the web is changing how we think.

(38:18) Focus on the work of David Nicholas’ CIBER team’s systematic studies into online behaviour. 40% people never revisit the same web page and that they view only three pages from the thousands available online.

The really big surprise is that people seem to be skipping over the virtual landscape … nobody seemed to be staying anywhere for very long … foxes are people that embrace all kinds of ideas like the wisdom of the crowd, bounce from here and there and pick things up and that’s how they acquire their knowledge. There there are hedgehogs. They like one big idea. They repeat. They go back to the same source. These people like the peer evaluated environment because they are certain of that.

AT 39.45 viewers were invited to take part in BBC/UCL CIBER study to try and identify whether respondents are foxes or hedgehogs to “help identify the impact the web is having on our brains“.

Reminder

In Ebooks what ebooks? (Auricle, 21 February, updated 24 February) I offered some reflections on the CIBER ebook studies.

The overall premiss of this last edition of Virtual Revolution appeared to be that people’s, particularly young people’s, brains are being remodelled by the web and the services such as Facebook that it supports. But as it entered its concluding 15 minutes Homo Interneticus employed the now deceased Marshall McLuhan’s voice from the 1960s to remind us that:

(42:14) We go on singing the same song of fragmentation and alienation because every society always looks at the preceding age while living in a new current one; never sees the age it is living in.

McLuchan’s ghostly reminder provides me with an opportunity to engage the neuronal pathways responsible for my own associative thinking by highlighting and blending in what others have said about our inclinations towards techno-neuroses. In my posting Technology Impeded Learning (TIL)? (Auricle 29 September 2009) I highlighted Martin Bean’s (Vice Chancellor of the UK Open University) keynote at ALT-C 2009. In his carefully crafted presentation Martin reminded us of how “moral panic” (my words) tends to exercise each generation of ‘elders’. To support his case at about 7: 20 and 7: 53 into his presentation he included earlier examples of how the “Fires of Hades” (my words) were supposedly going to be visited upon each generation by the ‘new’ technologies of the day.Note

ALT also offers other online videos of ALT-C keynotes .

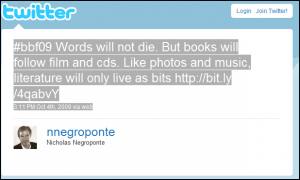

No reflection on the impact of media would be complete without including the technology researcher, commentator and futurologist, i.e. Nicholas Negroponte. Negroponte has many things to say about the future of media but I’m particularly interested with what he has to say about books, or more specifically ebooks (there’s that associative thinking again :)) His own Twitter feed is as good an entry point as any.

Or sample the following extract from an October 2009 US TV interview when Negroponte was asked about the future of books. He says:

Note

There is also a transcript of the 2009 Boston Book Festival interview referred to in the video piece which includes:

Books and stories are the classic example of medium and message, container and content. The two are easily confused. Confusion is amplified by an historical and concurrent event, the undoing of the publishing industry as we know it. The Boston Book Festival has a technical session that is distinctly about the future of reading, not the future of publishing. Note that the future of reading is not only driven by a deconstruction of the physical book, it is affected by social media, wherein reading itself becomes a social experience, as well as a personal one. (Nicholas Negroponte, 2009)

Negroponte’s view has been consistent. For example in The Future of the Book (Wired, 1996) he wrote:

The word is not going anywhere. In fact, it is and has been one of the most powerful forces to shape humankind, for both good and bad … There is no question that words are powerful, that they always have been and always will be … But just as we seldom carve words in rocks these days, we will probably not print many of them on paper for binding tomorrow. In fact, the cost of paper (which has risen 50 percent in the past year), the amount of human energy required to move it, and the volume of space needed to store it make books as we know them less than the optimum method for delivering bits. In fact, the art of bookmaking is not only less than perfect but will probably be as relevant in 2020 as blacksmithing is today.

Take a momen to reflect on that statement “The word is not going anywhere” and consider whether we should panic less. Or is Negroponte et al wrong?

For those interested in Negroponte’s thinking and the evidence which he uses to back it up, his 1996 work Being Digital is still worth a read if for no other reason than that readers can verify how accurate he has been in his projections. The time poor may be interested in this site which quotes liberally from that book. Negroponte’s 1993-1998 monthly columns for Wired are also available from his MIT site (Negroponte was a founder investor of Wired).

In these three postings (including today’s) we have veered between the arguments of the techno-utopians and techno-dystopians. Ok, allow me a bit of hyperbole.

History can perhaps inform how we should think and so make us better thinkers but never be allowed to dictate what we should think. Each generation needs to find its own answers suited to its own time and context and so it is for the current generation.

However, one thing that is dramatically different from previous techno-social “Tipping Points” is that the speed of innovation and opportunity with this one is just so great that identifying and gathering the evidence of impact (expected and unexpected, positive and negative) assumes a control of variables and events that may not exist. Echoing McLuchan this means we inevitably up end up looking back about how what we do, live and learn has been transformed by our technologies. The challenge therefore is for us to try and beat whatever technological swords exist into ploughshares and use them constructively.

At the moment, however, the internet and particularly the web is still like a gold rush in which the bigger or more corporate prospectors or actors on this stage risk making it more difficult for the micro-entrepeneurs or new techno-idealogues to bring forward solutions . The nascent ebooks, emagazines, enewspapers and even the ejournals market is a particularly interesting example in this landscape; these after all are, or have been landscapes populated mainly by words. In the physical world we can buy these media from whoever and wherever we like; but, yet, in the digital world we are expected to accept restrictions on what device we must view our content on, whether it is actually our content at all, or where we can purchase the content. This is only possible because in this world an ebook, emagazine, enewspaper, or ejournal article is no longer a physical entity; it is is collection of ephemeral digital bits temporarily masquerading as the desired physical analogue via aggregations of pixels on a display. Negroponte is right, words are not going anywhere. But in the ebook and other content landscapes vested interests are desperately trying to control how those words are represented, accessed, owned, disseminated and purchased. That’s why we need to see open formats like .epub become the norm That’s why Amazon’s attempts to lock users into their proprietary ebook format should be consigned to history. That’s why it’s good to see other ebook stores like Kobo (who offer .epub format content) are now on the scene so that users can have more choice. But at the same time there is definitely a lesson to be learned from the iTunes store in that it makes finding, and yes, sometimes purchasing content such an easy process. The enewspaper, emagazine and ejournal worlds also have something to learn here. As should everyone who is concerned about how we have currently modeled learning environments for the digital world; the current crop are in desparate need of a complete rethink.

Finally, I’m reflecting a lot lately on where all this apparent technological progress is, or has been, taking us. In this posting we can see that the technological promise is tinged with some concerns about the less welcome impacts of such apparent progress. I sit with my smartphone and marvel that I no longer need to expend physical energy in acquiring a book or newspaper and that the ‘words’, as Negroponte argued they would, are now flowing to me ever more efficienty. I also reflect, however, on the rapidity with which I have changed a lifetime of behaviour and the eventual impacts on others, because I have become part of a social aggregation of such changed behaviours; as beleagured newsagents and booksellers will testify. I also reflect on whether I am reading differently and shallowly as David Nicholas’ CIBER team has highlighted or whether I am just being more efficient in how I read. Indeed, is it reasonable for the act of reading to be based only a model of reading arising from a different time, place and technology, i.e. a country of old readers? But even surrounded by all the rich media possibilities I also continue to reflect on the marvellous efficiency of words for representing knowledge and meaning. The multiple quotations in this posting are an example. The video or audio material from which they came represented considerably more time viewing, active listening, and transcribing on my part than it will take any reader of this posting to “consume” them. Many gigabytes of video material can be represented by a few megabytes of words. Many megabytes of audio can be represented by a few kilobytes of words. While I would not have eschewed watching the video material because it accessed a different learning pathway in my brain, activated my emotional centres, and so stimulated the idea for this posting, in pure efficiency terms, however, the words win hands down. Another reason why, if the BBC is serious about its educational mission is should provide more transcripts like its US NPR counterpart.

But the really uncomfortable question my own posting has raised for me is whether this is pure hard technological determinism at work or something else? A question I touched on in my contribution (chapter 3) to the recent book Transforming Higher Education Through Technology Enhanced Learning. The weighty matter of technological determinism, however, will have to be the focus of a future Auricle posting.